Currently, many people know that around two thousand workers are dying at their workplaces every year. But where can we find the details of workplace injury statistics? Incidence and mortality of workplace injuries for the last twenty years classified by industry or gender can be found at the Korean Statistical Information Service, the portal webpage of Statistics Korea. The Ministry of Employment and Labor (MOEL) also publishes an annual report on workplace injuries including general status of workplace injuries and key characteristics. These reports show the viewpoint of MOEL on each area of workplace injury statistics.

On April 27, 2020, MOEL released the report on workplace injuries in 2019. The number of deaths was 855 from traumatic accidents and 1,165 from illnesses. Total number of deaths was 2,020, which is decreased by 122 from the previous year. Deaths from traumatic accidents have reduced dramatically. The mortality rate has also dropped from 1.12 per 10,000 workers in 2018 to 1.08 in 2019. While the mortality rate from illnesses rose, the mortality rate from traumatic accidents declined to 0.46, almost 10% of reduction.

However, it is still not enough to achieve the goal of the government to reduce the fatal accident rate at workplace by 50% by 2022. This concern grows when you look into the details of deaths from traumatic accidents.

Did the policy contribute to the decrease of fatal accidents in the construction industry?

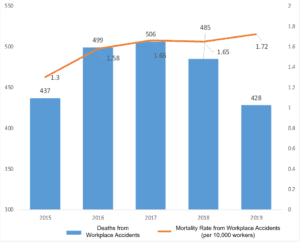

In early January 2020, MOEL vigorously promoted that the number of deaths from workplace accidents had decreased by 116 in 2019 from 2018, which was the biggest annual reduction since 1999 when the statistics on workplace fatal accidents had been adopted. The Ministry also announced that deaths from traumatic accidents in the construction industry were reduced from 485 to 428 thanks to its ‘workplace supervision concentrating on selective focus’ and ‘field-oriented enforcement’. MOEL also emphasized that its ‘field patrol’ had been successful even before the actual mortality rate from traumatic accidents was calculated.

The actual report on workplace injuries in 2019 showed different results from what the Ministry had announced. It was true that the number of deaths from traumatic accidents in the construction industry had decreased. But the mortality rate was elevated from 1.65 per 10,000 workers to 1.72. The number of deaths from accidents was reduced, not because of effective preventive policies but because of depressed construction industry activity. Traumatic fatality in the construction industry appeared to decrease simply because the size of workforce decreased.

The number of construction workers covered by workplace injury compensation insurance in 2019 was smaller by 450,000 than in 2018. That is why the number of deaths in 2019 was reduced by 57 compared to the previous year, while the mortality rate became higher. In 2019, 428 construction workers died from traumatic accidents at their workplaces. It would have been 410 if the mortality rate was the same as the previous year. In other words, eighteen additional workers lost their lives in 2019.

In addition, the construction industry was the main target of policy measures to reduce fatal accidents in workplaces. Since 2018, MOEL and the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA) have concentrated on prevention of fatal accidents with a focus on falling from heights, emphasizing the use of safe scaffolds in the construction industry. While the number of deaths from traumatic accidents in the construction industry in 2018 fell by around twenty, the fatality rate from accidents did not decrease.

In early 2019, MOEL stated that it was too early to see the effect of preventive measures in the construction industry which had begun only after May 2018. On the other hand, it commented that its safety management of tower cranes had achieved reduction goal of fatal accidents. According to MOEL, traumatic fatality was actually decreasing but it looked like being increased superficially, simply because more cases had been recognized due to the extended coverage of workers compensation insurance or because the statistics included cases in which the survivors received insurance benefits in 2018 for deaths that had happened in 2017.

Back then, we demanded MOEL’s sincere interim review on its preventive measures in the construction industry. Even when the total number or rate of mortality from accidents in the construction industry had not improved, it was necessary to check the selective focus of MOEL on falls from heights. It was also important to analyze in which types of workplaces the MOEL’s measures worked effectively and what was the evidence to anticipate those measures would be effective in the future.

Assessment based on Policy Goals, rather than Simple Statistics

However, MOEL just continued the same policies focusing on prevention of falls from heights by encouraging ‘systematic scaffolds’ and workplace patrols without any analysis. The mortality rate from traumatic accidents in the construction industry has not been reduced yet. Rather, it has been elevating for the last five years. With no clear explanation on the goal and outcome of the workplace patrols, we can only evaluate based on currently visible statistics. There is no evidence to continue the current preventive measures focusing on the construction industry or workplace patrols, unless traumatic deaths in the construction industry show meaningful reduction.

There are different opinions about this issue. Some propose not to criticize the government too much since this is the first time for us to have a detailed strategic goal in an occupational injury prevention policy. Some say that it is a short-sighted view to criticize the policy only because it does not make any visible effectiveness in one or two years. There is an argument that we need to put more budget and manpower because the lack of administrative resources is the causes of ineffectiveness even though MOEL and KOSHA try to make a new approach to prevent workplace injuries. Another argument says that the increase of traumatic mortality rate in the construction industry is just an illusion because the workers compensation insurance statistics do not reflect the actual number of construction workers.

It is plausible that the absolute number of deaths from traumatic accidents in the construction industry has reduced. However, it is very clear that the arguments above should be supported by a sincere analysis of the effectiveness and loopholes of the current preventive measures of MOEL and KOSHA. What we need is not a fragmented ‘fight’ about immediate change in or adherence to the current strategy, but a high-quality assessment, evaluation, and discussion focusing on what should be done to fully protect workers’ lives.

Reduction of Deaths Resulting from Changes in the Industrial Structure

The total number of traumatic deaths in workplaces seems to be decreasing due to the effect of decreasing proportion of high-risk industries rather than the effect of policies to prevent accidents. The proportion of low-risk industries which have lower traumatic mortality rates than average has decreased continuously from 56.2% in 2017 to 57.7% in 2018, and to 59.7% in 2019. This change in the industrial structure brought a natural decline of traumatic deaths in workplaces even without any special improvement in preventive policies or safety measures.

In fact, forestry, mining, and construction sectors which already had high mortality rates show even elevated mortality rates. Mortality rates in other industries including manufacturing do not change much. Transportation·warehousing·communication and ‘others’ are the two categories that show decreased mortality rates, and the mortality rate of ‘others’ was originally low.

When the changes of industrial structure are considered, the number of deaths from traumatic accidents in workplaces in 2019 would has been 893, which was a decrease by 78 compared to 2018, even if the traumatic mortality rate in 2019 was assumed to be the same as one in 2018. The actual number of deaths from workplace accidents in 2019 was 855. Although MOEL emphasized its achievement in reduction of 116 deaths compared to the number in 2018, only 38 deaths can be claimed to be additionally prevented by the enforcement and policy intervention considering the natural reduction of 78 deaths. Similar features can be found in the extended analysis of statistics from the last three years. Changes in the number of deaths and mortality rate from traumatic accidents in workplaces look to be mainly due to the changes in industrial structures, not workplace safety improvements.

Workers’ Safety is the Goal of Workplace Injury Statistics

It is our goal to make workplaces safer and healthier, not to make the workplace injury statistics lower. Sometimes we may not be able to achieve specific reduction goals in workplace mortality rate or incidence rate in specific time periods. Because it could be difficult to change the practices that prioritize efficiency and profit over workers’ health and safety and it could take time to see the effects of policies, even when appropriate ones are implemented. However, even in that situation, we need to analyze various indicators, figure out why the goals could not have been achieved, and set up new action plans. If a certain policy should be kept even when its goal has not been achieved, we need to convince others to maintain that policy.

MOEL and KOSHA should assess their workplace injury preventive policies and the target indicators since 2018. The government’s strategies and tactics should also be analyzed. In addition, they need to propose future direction of preventive policies based on those assessment and analysis. They need to listen to the voices of construction workers and labor unions which keep saying ‘big issues’ such as enacting the Workplace Manslaughter Act and eradication of illegal outsourcing in construction sites. Not only technical approaches such as workplace patrols and systematic scaffolding but also those voices should be reflected in policies. MOEL should change its viewpoint of workplace injury statistics.