In the era of the climate crisis, key words for worker health: Right to stop work and reduce working hours

Min Choi, MD

Activist and occupational and environmental medicine specialist

Korea Institute of Labor Safety and Health

The climate crisis also affects workers’ health. Representative examples are heat-related diseases such as heat stroke and heat exhaustion. These occur when the human body is exposed to high temperatures and has problems regulating body temperature. Construction workers, mobile workers, agricultural workers, and transportation workers who work outdoors are easily exposed to high temperatures in the summer, and high temperature exposure situations are becoming more frequent with climate change. Exposure to high temperatures not only has health effects due to direct heat illness, but can also increase fatigue and reduce concentration, increasing the risk of accidents or injuries at work. In the future, the indirect effects of exposure to high temperatures should also be further studied.

There are quite a few cases of heat-related illnesses occurring indoors. A representative example is the struggle of workers at Coupang’s logistics center in South Korea last summer, demanding the installation of air conditioners and maintaining an appropriate indoor temperature. According to data released by Coupang’s labor union, the average temperature of the distribution center is 31.2℃ and humidity is 59.48%. Packing workers at supermarket stores also work under similar conditions. One worker said, “When I pack items with two large fans without air conditioning, I sweat so much that it is difficult to work. Last summer, one of my fellow workers collapsed, and all I thought was that he or she was too hot.”

The health issues of emergency personnel who must respond to extreme climate events, such as emergency/paramedics and firefighters, are also an important occupational health topic related to the climate crisis. Workers who fight forest fires, such as firefighters or special fire extinguishing personnel, are at high risk of overwork as they use heavy equipment and protective gear to perform tasks that require a very high physical strain for long periods of time. During the process of extinguishing forest fires, they may be exposed to harmful substances such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or respiratory irritants, and the risk of musculoskeletal disorders and injuries is high. After heavy rain, the possibility of developing infectious diseases and skin diseases during work increases. There is a high possibility of being exposed to stress or trauma during the process of rescuing victims or damaged animals.

The climate crisis has many faces and the right to stop work is needed

It is impossible to properly take care of workers’ health in the face of the climate crisis by responding one by one to these various problems as they arise. This is because the impact of the climate crisis always comes in a direction and magnitude that exceeds our predictions. In this era of an unpredictable climate crisis, one of the keywords to protect workers’ health is the right to stop hazardous work.

The current Occupational Safety and Health Act clearly states that workers may, “stop work and evacuate if there is an imminent risk of an industrial accident occurring.” It is easy to think that this right to stop work can only be used right before an industrial ‘accident’ occurs, but it can and should be used in various dangerous situations due to the climate crisis, such as cold or heavy rain. There are already similar cases in the United States. For example, there was an incident in 1962 when seven workers left the workplace to protest because the temperature was too low. When the employer disciplined the workers, a U.S. court ruled that the employer had committed unfair labor practices.

However, exercising the right to stop work on site is not easy. On March 16 of this year, an accident occurred at an apartment construction site in Incheon where a 2-ton gang form being lifted by a tower crane was blown by the wind and hit the windshield of the tower crane’s cockpit. Although there were no casualties, it was an extremely dangerous situation.

The contractor’s explanation was that at the time of the accident, the wind was blowing at an average speed of 3.2 meters/second, which is less than the 15 meters/second standard for work stoppages. However, the workers claim that there was a momentary gust of wind at the site at the time, regardless of the average wind speed. However, in the face of labor union suppression, they failed to actively refuse dangerous work.

Park Se-jung, head of the Occupational Safety and Health Department of the National Construction Workers’ Union, noted that, “It is said that workers’ right to stop work is guaranteed under the current Industrial Safety Act, but as seen in this accident, it is not easy for workers to be the first to say ‘it is dangerous to work today’ at the site.” Park emphasized that, “In order to prevent accidents, it is essential to change awareness to respect workers’ judgment and allow workers to have the right to make decisions about their work.” These changes will become more important during the climate crisis, when various unpredictable risks will become more frequent.

Reducing working hours and demands for climate justice

A representative labor-related topic discussed in the existing climate justice movement is the reduction of working hours. Working less not only reduces the absolute amount of resources used as part of the labor process, but also reduces the amount of carbon-intensive consumption that follows the ‘labor expenditure’ cycle. This is because long working hours also lead to consumption with a high carbon footprint, as seen in the daily experience of going to work early in the morning and leaving work late at night, and eating delivery food because you are too tired to cook. Those who advocate shortening working hours in terms of climate justice say that the struggle to reduce working hours, which has been a ‘fight to win free time’, is a struggle for social and environmental justice, and that we should work less to save the earth and our future.

The British environmental group, Platform London published a report saying that if the UK switches to a four-day work week, greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced by 127 million tons per year by 2025. This is taking into account the reduction in driving distance to and from work due to the switch to a four-day workweek, and the reduction in power consumption for office lighting, elevators, and heating and cooling costs due to a reduction in daily work hours. This is a huge amount equivalent to 21.3% of the UK’s total annual greenhouse gas emissions.

There is already quite a bit of research showing that reducing working hours can increase sustainability by reducing ecological pressures on economic output and consumption patterns. A study that explored working hours, ecological footprints, carbon footprints, and carbon dioxide emissions in 29 OECD countries using data from 1970 to 2007 found that long working hours increase ecological pressure even after adjusting for other factors. Therefore, the researchers suggested that it would be appropriate to promote reduction of working hours as one of the policy goals to increase environmental sustainability.

However, in South Korea, it seems that the movement to reduce working hours has not yet been discussed in terms of climate justice. In the current situation, where even the cap on overtime work at 52 hours a week is being challenged, the connection between the immediate issue of long working hours and climate justice may seem too distant. However, there are clues about how this issue is moving forward.

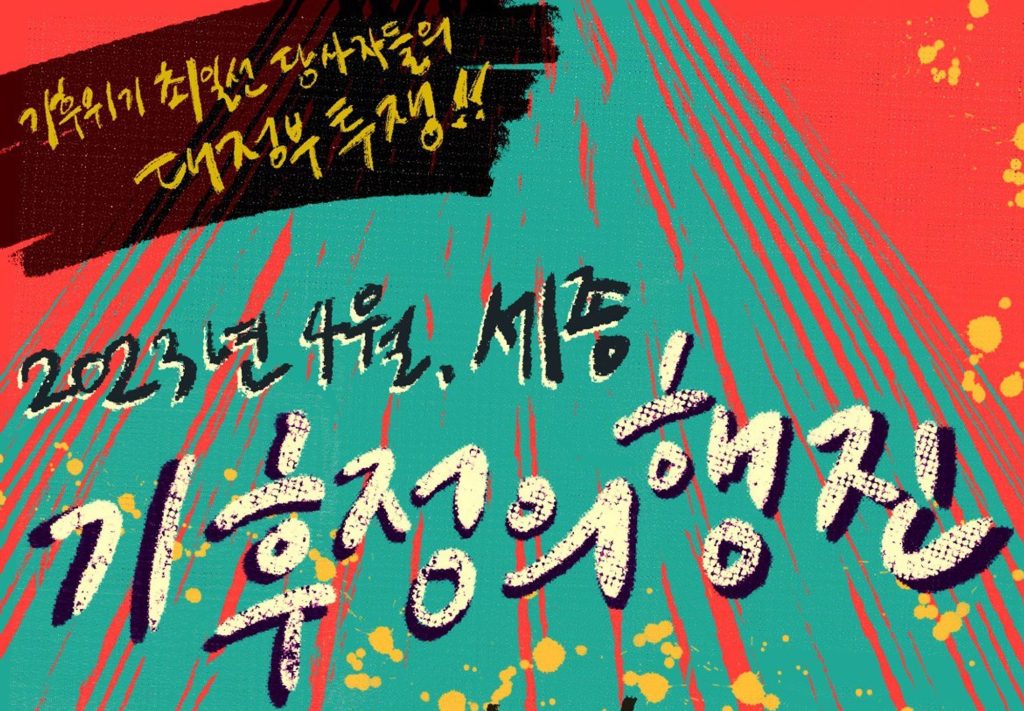

Supermarket workers will participate in the climate justice strike on April 14th. In accordance with the Distribution Industry Development Act, the mandatory holiday system for large supermarkets, which has been on the principle of two public holidays a month for over 10 years, is under threat by the Yoon Seok-yeol administration. Attempts are being made in the cities of Daegu and Cheongju to change mandatory closing days from weekends to weekdays. In response, service workers who want to keep Sunday’s mandatory closing day argue that the mandatory closure should be expanded to the entire large distribution industry, such as department stores and shopping malls, and that the fast-growing night-time distribution industry, focusing on non-store retailing, should be regulated. This is a concrete implementation of the slogan mentioned above, ‘Let’s work less to save our future and the planet.’

The move to change large supermarkets’ mandatory weekend closures to weekdays or to ease restrictions on night business hours is a policy aimed at increasing working hours, strengthening the 24/7 system, and promoting consumption. Supermarket workers decided to participate in this strike to publicize the significance of the struggle to change mandatory non-working days for large supermarkets.

“Union members also welcome the explanation that preventing changes to mandatory non-working days is related to the climate crisis, and we want to actively give it meaning,” said Bae Jun-kyung, policy director of the Supermarket Industry Workers’ Union. “By participating in this strike, we look forward to sharing the issue of workers’ right to rest with many environmental movement groups.”

The climate crisis is literally eroding humanity’s foundation for survival. Almost all challenges facing humanity are connected to the climate crisis. In particular, the workers’ health rights movement, which seeks to protect our bodies and minds against unbridled capital, can lead to action to prevent the climate crisis in that it puts a brake on capital that has been accumulating profits by exploiting the earth and its ecosystems. This April, let’s shout out for climate justice together with voices demanding workers’ health rights.

Comments