Globalized Organization and Resistance in the Digital Economy

Min-gyu Oh, Director of Labor Issues Research Institute, Liberation

Translated by Michelle Jang

Reviewed by Joe DiGangi

Korea Institute of Labor Safety and Health

“The Fourth Industrial Revolution and changes in the way we work have created a digital workforce that is completely different from the traditional workforce.”

“It will be easy to find jobs and someone to work, so it will be difficult to organize unions or strikes.”

Until very recently, these stories were considered common sense. But as the pace of digital transformation accelerates, more workers are starting to wake up, and their organization and resistance are spreading around the world.

The first sector to start organizing was platform workers in the mobility sector, such as delivery riders and taxi app drivers. Initially, organizing and resistance were repeatedly unsuccessful. Only a small number of riders and taxi app drivers were organized into unions, and there seemed to be many workers around them who would be willing to take their place if they went on strike.

The all-out resistance that began with the pandemic

However, the efforts of delivery riders and taxi app drivers to organize and resist did not stop. In particular, as the pandemic ended and delivery calls decreased, platform companies immediately began to slash delivery fees, which led to a wave of worker resistance in 2022.

In January 2022, UK delivery riders went on strike. Their strike lasted for over half a year. The riders were furious because the delivery platform ‘JustEat’ and the delivery agency ‘Stuart’ cut the basic delivery fee by as much as 24%. During the pandemic, they were praised as ‘essential workers,’ but after that period, they were treated as disposable consumables.

Similar situations happened in various places, and resistance became globalized. In 2024, there were strikes and mass protests by delivery riders in Turkey in February, Myanmar in March, Portugal in April, Dubai in May, the Netherlands in June, Germany in July, Malaysia in August, France in September, and Italy, South Korea, Thailand, and Hong Kong in October. In South Korea, the Riders’ Union and the Delivery Platform Union negotiated more than 20 times after Coupang Eats cut delivery fees, but there was no improvement, and they went on strike twice in October of the same year.

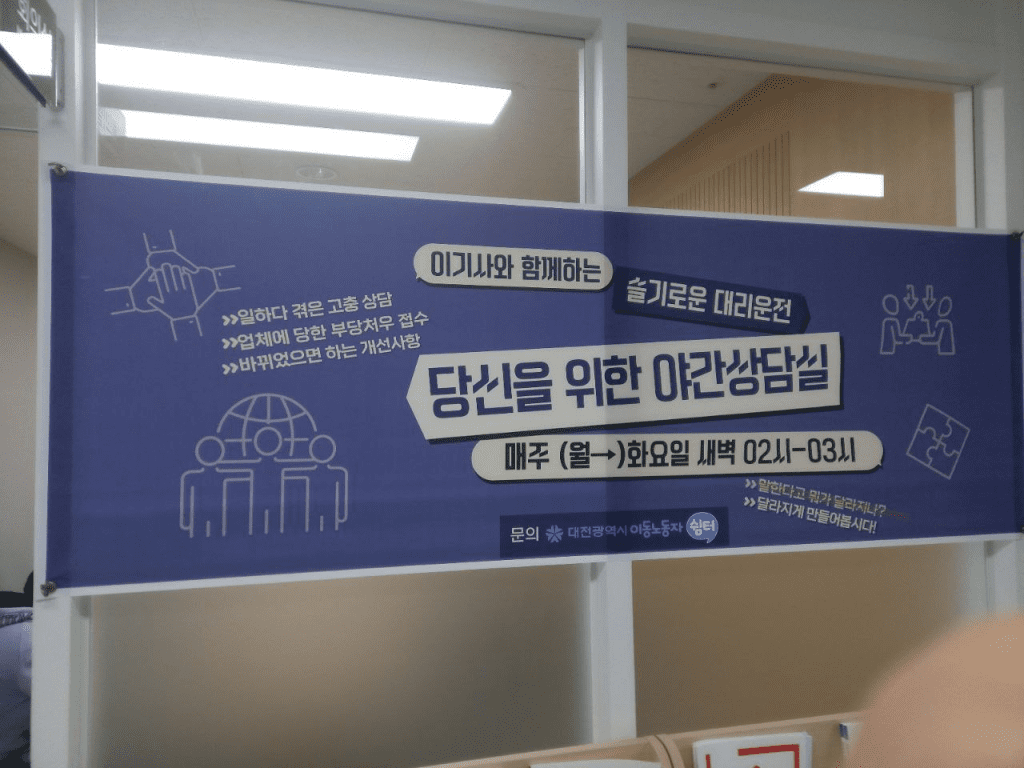

The riders’ organization and resistance movement soon expanded to the taxi app driver sector. In 2024, ride-sharing app drivers, including Uber, also organized strikes in South Africa (August) and Kenya (October). In South Korea, proxy drivers also began to fight against Kakao Mobility.

Reveal the algorithm!

In October 2022, a 26-year-old worker died in a traffic accident while delivering in Italy. The platform he worked for, Glovo, sent the following message to the deceased’s email account 24 hours later: “We regret to inform you that your account has been suspended due to non-compliance with the terms of your contract.” It was a robo-firing (automatic deactivation) for failing to complete a single delivery due to his wrongful death. In response to the absurd means of using AI and algorithms to grade and rate workers and then suspending or discontinuing accounts if they are not satisfied, digital workers have formalized the demand for ‘disclosure (explanation) of the algorithm.’

Uber drivers in the UK and other ride-hailing app taxi drivers have started organizing resistance against platform companies’ algorithms and abuse of personal information by forming a labor union and creating the ‘Workers Info Exchange.’ As a result, a Dutch court recently recognized the right to access Uber and Ola’s automated decision-making and the right to explain the algorithms. In the rider sector, the Palermo District Court in Italy recently ruled that Uber and Ola must explain and negotiate with unions about algorithms that affect working conditions.

Algorithms and personal information (data) are inseparable elements that digital companies use to generate profits and control workers. Personal information is not just a name, social security number, phone number, and address, but also encompasses the vast amount of data that digital workers create through their labor. How many calls do app drivers make a day, where do they go, how much does it cost, which calls are accepted and which are rejected, etc.

Based on this data, they train the AI that powers the algorithms, and create algorithms to maximize the profits of digital companies and squeeze the most out of digital workers. A good example is Uber, which recently succeeded in turning a profit after a decade of losses, by introducing new algorithms to utilize dynamic pricing and up-front pricing.

Guarantee our rights to the data we create!

A management consultant named Len Sherman wrote in Forbes, a business magazine in the US, that Uber’s new fare system did not change the cost to customers, but drivers’ earnings significantly decreased, and Uber’s profits increased by the same amount, proving with specific figures that digital companies are exploiting digital workers using algorithms and personal information (data) to extract profits.

Accordingly, digital workers are also raising new issues related to the protection of their own personal data. Recently, the Dutch Data Protection Authority (DPA) imposed a fine of 10 million euros (approximately 14.2 billion Korean won) on Uber. Around 170 French Uber drivers filed complaints and petitions against Uber, claiming that Uber did not specify or disclose to drivers how long it would keep their personal data and how it would protect their personal data when transferring it to corporations in countries outside of Europe.

Earlier, the Italian Data Protection Authority (DPA) also imposed a fine of 2.6 million euros on the delivery platform, Globo, in 2021 for violating riders’ data protection rights. Globo is a Spanish subsidiary of Delivery Hero, which confirmed that all of its affiliates freely access the personal information (data) of riders in each country. It is also reasonable to suspect that Delivery Hero’s South Korean subsidiary, Baedal Minjok, is also sharing the personal information (data) of South Korean riders around the world. All these issues would be impossible to raise without the unionization and collective resistance of digital workers.

In South Korea, the proxy driver union signed a collective agreement with Kakao Mobility at the end of 2022 after two years of negotiations and struggle, which included the right to negotiate algorithms by stipulating that the company would “explain the main contents of the (vehicle) allocation policy to the union and seek reasonable solutions together for matters that both labor union and management jointly recognize as requiring improvement.”

The Riders Union and the Delivery Platform Union also changed the algorithm for calculating delivery fees based on straight-line distance that Baedal Minjok had been implementing to one based on actual distance after persistent complaints and struggles. In collective bargaining with some regional delivery agencies, they included the clause that ‘unilateral account suspension (blocking of app access) will not be implemented.’

Fighting against the digital industry, which ranked number one in industrial accidents

With the rise of platform companies, the undisputed No. 1 company in industrial accidents in South Korea is now ‘Baedal Minjok.’ Following the delivery platform companies, e-commerce industries such as Coupang Logistics Center, and mobility industries such as proxy driving and taxi apps are also following close behind. The digital industry is causing the most industrial accidents.

However, worker compensation insurance systems and occupational safety-related laws are geared toward traditional workers, and often do not apply to digital workers or do not work properly. A typical example is the ‘exclusivity standard’ in South Korea’s workers’ compensation law. This is a system that requires workers to provide labor to only one employer to be eligible for workers’ compensation insurance. In cases where work is received through multiple apps, the worker is not covered by workers’ compensation.

In 2022, the Riders’ Union in South Korea fought and succeeded in abolishing the exclusivity clause. As soon as it took effect in July last year, an additional 500,000 delivery riders and proxy drivers were included in the workers’ compensation insurance system. This led to the inclusion of many more disenfranchised workers, including not only platform and digital workers, but also those who have two jobs or more. When the rights of platform workers are guaranteed, the rights of traditional workers are also improved.

Globalized organizing and resisting of digital workers

In Europe and the United States, care and domestic work platforms are already rapidly increasing beyond mobility platforms, and it is said that there is a possibility that the organization of the care sector may go beyond mobility platforms. South Korea will soon be experiencing the same wave of change.

There have also been attempts to organize these workers, as it has become clear that large-scale language model AI training, such as ChatGPT, uses large amounts of low-wage labor for data collection, data correction, and data labeling. ChatGPT and Facebook have been outsourcing the labor of ‘content moderators’ who are used to exclude hateful and provocative data to Kenya for only $1-2 per hour, and in May of last year, 150 moderators gathered in Nairobi, Kenya, and formed the ‘African Content Moderators’ Union. Recently, even in South Korea, Natepan content moderators have started to form a union, and the organization and resistance of digital workers are rapidly globalizing. The message they are sending to the world is very clear.

“We are just newcomers, and we are no different from traditional workers. Do not discriminate against us in the Labor Standards Act, the Industrial Safety and Health Act, the Serious Accidents Punishment Act, and in social insurance.”

Comments