The power that bypassed Chung-hyun Kim and the power that brought him down (Aug. 2025)

Ju-hee Jeon

Korea Institute of Labor Safety and Health

The Countermeasures Committee for Chung-hyun Kim

Translated by Michelle Jang

2025

This article explores the forces that could have saved Chung-hyun Kim, a contract worker at a power plant, but didn’t—and the ones that ultimately crushed him. It asks: where did those forces come from?

The power that overwhelmed Chung-hyun Kim: His own extraordinary effort and skill

Chung-hyun Kim, a contract worker at a coal-fired power plant, started his commute at 6 a.m. A few years ago, he moved to Boryeong to live with his mother, and since then, it took him over an hour to get to work. He arrived early at the machine shop of the Taean Thermal Power Plant. Inside, six lathes were spread out across the room, with a small desk tucked in between. There, before the workday began, Kim sat down to plan his tasks, read the pages he did not finish the day before, and study for certification exams.

What drove Chung-hyun Kim to earn 12 certifications in his lifetime? Was it a desperate will to escape the harsh reality of being a second-tier subcontractor at the very bottom of the power plant hierarchy? Or was it his personal effort to survive the looming threat of job loss as the plant approached closure?

In truth, Kim lived with constant anxiety over the plant’s shutdown. As a second-tier subcontractor, he both endured and resisted the exploitation he faced—submissive at times, but fiercely outspoken at others. He appealed to foremen at KEPCO KPS (Korea Electric Power Corporation – Plant Service & Engineering Co., Ltd.) with whom he was close, asking for help and raising concerns about his unfair treatment. When a new subcontractor president slashed wages, Kim protested—and was fired. Even then, he clung to his goal, continuing to earn certifications with relentless determination.

However, listening to his old hometown friends and former colleagues, it became clear he had loved working with machines and reading books ever since he was a child. I nodded along politely when they spoke, but deep down, I assumed it was just a romanticized memory of someone who had passed.

It wasn’t until I received the forensic data from his phone—call logs, and hundreds of thousands of KakaoTalk and text messages—that I truly understood. He was someone who loved assembling machine parts, creating something out of fragments.

His KakaoTalk messages were filled with conversations about machines—detailed, constant, and passionate. There were excited notes about a machinery competition he had attended, messages full of pride when he earned a new certification, and frequent requests from people around him to build things they needed in daily life—requests he never turned down.

To him, being a secondary subcontractor at a power plant and being a power plant worker were two entirely different identities. The machine shop was his world—a space where his childhood dream of working with machine parts came to life.

It was only then that I realized that Kim Chung-hyun was not simply a “wage laborer,” a source of profit and exploitation under modern capitalism. In that space, Chung-hyun Kim existed as a homo faber—a maker, a craftsman, and someone who found dignity and meaning in the act of creation.

On the other hand, the machine shop was owned by Western Power and formally “leased” to KEPCO KPS, creating a clear separation between owner and user. There, Chung-hyun Kim’s diligence and technical skills as a homo faber became fertile ground for excessive exploitation. The standard practice for lathe machines is “one person per lathe.” When the Chairman of the National Assembly, Won-sik Woo, visited the accident site, KEPCO KPS was not entirely wrong in saying that “it is difficult for a team of two to handle this work.” However, the workshop contained six lathe machines, which—according to KEPCO KPS’s own logic—should have required six workers. Yet, Chung-hyun Kim was working there alone. We investigated the machine tool rooms at other manufacturing sites, where 11 lathe machines were operated by 13 workers—meaning they had two extra workers to maintain the “one person per lathe” standard.

Chung-hyun Kim was trapped by his advanced skills. Simply lacking a four-year college degree led to the devaluation of his abilities, which may have driven him to pursue even more certifications. The prime contractor exploited his diligence and technical expertise, pushing him to take on increasingly demanding tasks. The rigid vertical hierarchy between the prime contractor and subcontractors pressed down even harder on the “skilled” Chung-hyun Kim. While the excessive workload constantly put him at risk, June 2, 2025, was an especially unlucky day.

The power that bypassed Chung-hyun Kim: The Labor Standards Act and the Yong-gyun Kim Special Committee’s recommendations

Article 9 of the Labor Standards Act prohibits intermediary exploitation: “No person shall, except in accordance with the law, intervene in another person’s employment for profit or gain profit as an intermediary.”

While this law was originally intended to prohibit labor brokerage, under neoliberalism it has ironically become the legal basis permitting such practices. The phrase “except in accordance with the law” effectively allows intermediary exploitation under legal frameworks like the Dispatch Workers Act.[1] Moreover, the public sector has fully embraced outsourcing, solidifying intermediary exploitation as a new norm through private consignment, service contracts, and similar arrangements.

After the IMF crisis, South Korea’s labor laws turned their backs on workers. The law was then wielded with even more blatant rhetoric. The so-called “rule of law” became little more than a tool to dismantle legal protections, enabling intermediary exploitation and legitimizing excessive labor exploitation. While the very language of the law was being distorted at its core, the government used administrative orders and guidelines to privatize the public sector under the pretext of “public sector efficiency.”

KEPCO KPS is a public enterprise shaped under the oppressive influence of these laws and government policies. Since the privatization of the power plant maintenance industry began in 2003, KEPCO KPS lost its monopoly in this sector. As of 2017, its market share in power plant maintenance had declined to 47%. However, privatization did not only disadvantage KEPCO KPS. It remains the only public enterprise in the field, a status that enables it to retain significant dominance and influence.

By leveraging government policies aimed at transferring its technological expertise to the private sector and fostering private companies, KEPCO KPS established a subcontracting system centered around small-scale, vulnerable firms, thereby securing its control and extracting excess profits.

After retirement, KEPCO KPS executives and employees either became presidents of subcontracting firms or gained the technical expertise required for small businesses to participate in bids, thereby establishing a lasting network of influence centered around KEPCO KPS. The president of Korea Power O&M, the company where Chung-hyun Kim worked, is also a former KEPCO KPS employee.

As the prime contractor’s control strengthens, the number of procedures flowing from the prime contractor to the subcontractors multiplies, yet these procedures are often overlooked in practice. Excessive paperwork-based safety management undermines the true importance of safety and dilutes warnings about risks. This paradox creates a situation where the more safety is emphasized, the more it ends up being neglected.

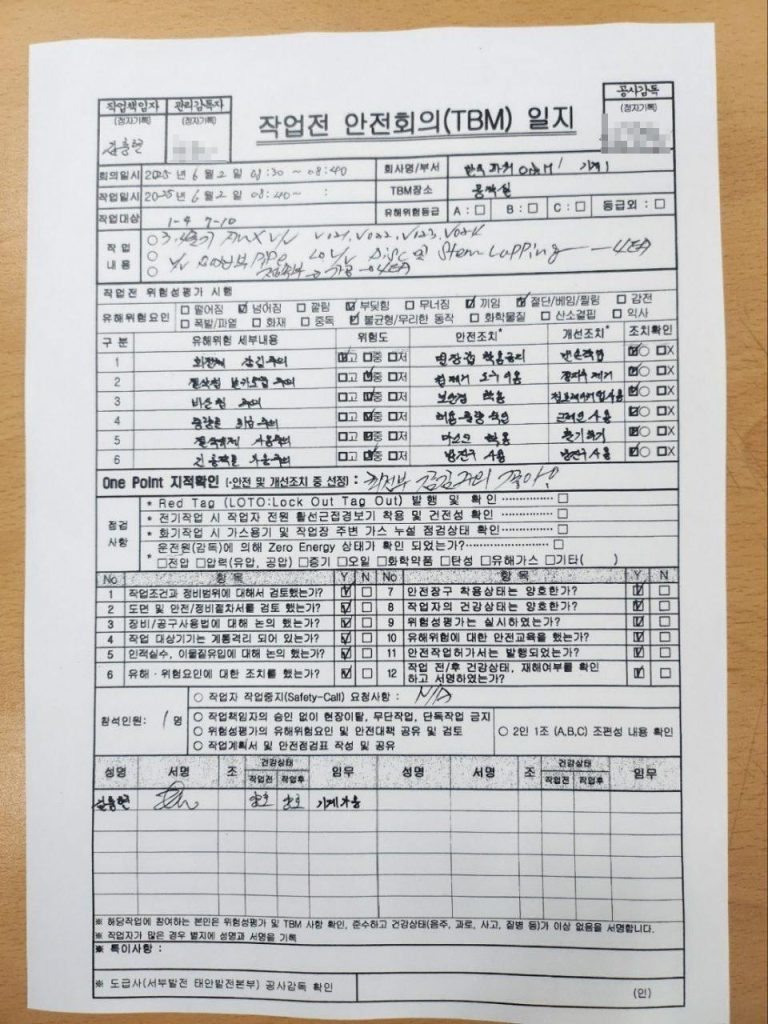

How did things change on the ground after Yong-gyun Kim’s death? For second-tier subcontractors at the very bottom of the power plant’s subcontracting hierarchy, it was little more than a passing rumor. Common comments included, “After Yong-gyun Kim died, all we got was more paperwork,” or “I thought they’d regularize us after Yong-gyun Kim, but it was just one meeting.” The much-publicized recommendations of the Yong-gyun Kim Special Investigation Committee never truly reached them. The committee recommended “direct hiring and regularization as a safety measure.” Chung-hyun Kim’s death exposed that these words were merely rhetoric circulating in society. Meanwhile, Chung-hyun Kim’s work was carried out without even proper TBM documentation. KEPCO KPS managers issued work orders to him via KakaoTalk, texts, and phone calls. After work, he had to go around getting the prime contractor’s signature on the TBM forms. Within this collapsed procedural system, hazardous work methods were neither properly reviewed nor filtered out.

What does “management” mean in a multi-layered primary and subcontracting structure?

On one hand, there are criticisms of the proliferation of management procedures and an overabundance of management personnel. Indeed, the “Yong-gyun Kim Report” pointed out a distorted structure where, after the split into the five power generation companies, there was a shortage of personnel needed for operations and only an increase in management personnel. On the other hand, a management vacuum is evident. Whether pursuing efficiency or safety, the day-to-day management necessary for these goals is not functioning. Indeed, this function is broken somewhere in the primary and subcontracting structure. Consequently, while there is a literal excess of “management,” it is absent where safety is truly needed.

At this point, it is worth revisiting our habitual use of the term “prime contractor-subcontracting structure.” What is the structure? The structure is formed by endless relationships: the relationship between prime contractors and subcontractors, between subcontractors, and between subcontractors and subcontracted workers. However, these relationships are not “connected.” They are a structure of countless connections characterized by disconnection and gaps. Therefore, isn’t a safety system encompassing the multi-layered structure of prime contractors and subcontractors merely an illusion? Or is the idea of a comprehensive safety system merely an ideology that obscures the true nature of this disconnected prime-subcontracting structure?

The type of accident experienced by Yong-gyun Kim and Chung-hyun Kim was “entrapment.” Immense forces crushed their bones and flesh, their lives and labor. I oppose labeling their accidents as simply “traditional accidents.” The gaps in labor laws created by neoliberalism were far too large for the Yong-gyun Kim Special Investigation Committee’s recommendations to fill. No “safety system” capable of plugging this enormous gap has yet been invented. In this sense, the “entrapment” of subcontracted workers represents a new and intractable risk. Regarding Chung-hyun Kim’s death, we have no better solution than those we face with the risks of nuclear power plants or the disasters caused by climate change. Therefore, as risk sociologists argue, we must stop the very production of such risks. This is why all legal powers enabling the “outsourcing of risk” must be halted.

[1] Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (2021) Joint Forum on Legal Measures to Eradicate Intermediary Exploitation, October 13, 2021

Comments