Why Are Women’s Work-Related Injuries Hidden? (Mar. 2025)

Jiyoon Jung, MD

Translated by Heeun lee

Reviewed by Joe DiGangi

Korea Institute of Labor Safety and Health

2025

It was July 2023. One day, while revising the manuscript for ‘Women Hurt at Work,’ an Excel file suddenly appeared on a public data portal (data.go.kr). It contained annual figures for the number of workers covered by workers’ compensation insurance and the number of applicants for workers’ compensation, broken down by gender.

Is the gender ratio of workplace injury 3:1?

Prior to July 2023, the only basic statistical data with gender breakdown in official workplace injury statistics was the Annual Analysis of Workplace Injury published by the Ministry of Employment and Labor. This annual report provides data showing how many men and women were approved for workers’ compensation categorized by industry, sector, and workplace size. The number of workers covered by workers’ compensation or the number of workers’ compensation claimants broken down by gender is unknown. The only available information on gender was the number of workers whose claims were approved. The only fact visible on the surface was that among those approved for workers’ compensation, men accounted for about 75% and women for 25%, and what this meant was open to interpretation.

Why do female workplace injury claims appear to be fewer than male claims? It might be because the number of women covered by workers’ compensation insurance is inherently low, or it might be because even when covered, women are less likely to file workers’ compensation claims. Alternatively, it could be that even when filed, claims of women workers might be less likely to be approved. It might also be because women genuinely work in safer environments. This sparse Excel file revealed that the gender ratio of workers covered by workers’ compensation insurance in 2020 was 56% male and 45% female, suggesting that the difference in coverage alone does not explain the disparity in workplace injuries by gender. The approval rate for workers’ compensation claims related to occupational diseases was 62% for men and 59% for women, indicating that it is difficult for both genders. Then, in August 2024, this data was updated and uploaded to the public data portal, excluding the number of insured persons by gender. It currently remains the only data source containing the number of workers’ compensation insurance claimants by gender.

Data Gaps and Women’s Work-Related Injuries

The Ministry of Employment and Labor explains that it publishes the Annual Analysis of Workplace Injury to understand the characteristics of workplace injuries and establish prevention policies. Examining the distribution of injuries by industry reveals that the most dangerous sector—ironically—is ‘other industries,’ where the largest number of recognized workplace injuries happened. In 2023, a staggering 27,000 out of approximately 34,000 female workers recognized as having work-related injuries (about 78%) were classified under ‘other industries.’ Among the total 102,000 male workers recognized, 24,000 (24%) fell into this category. Within this ‘other industries’ category, roughly 10,000 men and 10,000 women are injured workers belonging to the ‘wholesale, retail, food, and lodging’ sector. Also 8,300 women are listed as ‘professional, health, and education workers’—but what exactly do these people do?

The data gaps created by lumping too many people together under the broad category of ‘other industries’ hinder efforts to connect workers’ compensation statistics to prevention of injury within that specific industry. Since it remains unclear under what conditions and to what hazards workers in ‘other industries’ were exposed to when injuries occurred, the risks persist. Even this data only includes ‘workers whose claims were approved’ who were eligible for workers’ compensation insurance and were not hindered by various factors that prevent claims—such as fear of job instability or guilt toward coworkers, lack of awareness that their injury was work-related, unfamiliarity with the claims process, lack of time to wait for approval, or lack of resources to assist with the application—allowing them to appear as a single number in this massive table. Of course, no data exists showing how many of these individuals were able to receive adequate medical care and return to work, making a gender impact assessment impossible.

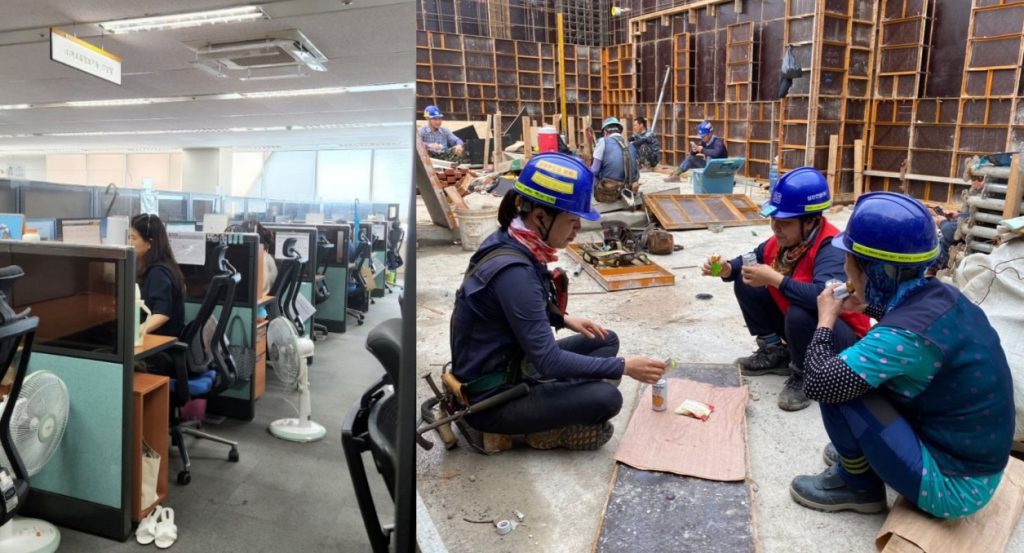

While numbers stitched together in unfriendly patterns create incomprehensible data, women work in shipyards, construction sites, call centers, cafeterias, at home as a remote workplace, and in other people’s homes. Women working in male-dominated workplaces often receive protective gear that does not fit properly. Women freelancers, positioned on the boundary of worker status, sometimes face employers—the very entities responsible for providing protective gear—who fail to recognize the need for it at all. Furthermore, women’s jobs which had traditionally been considered ‘easy and safe’ were often acknowledged as hazardous only after a long accumulation of fatal consequences like suicides, deaths from overwork, lung cancer, and blood cancer.

Why are the lives of women who get sick from work so poorly understood?

Capitalism has addressed the problem not by adapting the work environment to the worker’s body, but by finding workers suited to the job. It seeks to maintain the system by recruiting workers who will labor without complaint under poor and unfavorable conditions, and who can endure humiliation while experiencing unreasonable treatment. This is evident even in the discussion that began with the proposal: “To hire a childcare helper in Korea costs 2 to 3 million won per month, while a foreign domestic helper in Singapore costs around 380,000 to 760,000 won per month, so let’s introduce foreign domestic workers.” This move aims to replace the positions that middle-aged and older women have held while enduring low wages, unstable employment status, and unfair treatment with workers in even more vulnerable positions. Consequently, for vulnerable workers occupying these marginal jobs, endurance becomes routine. It remains difficult for workers to speak out, despite the fact that poor working conditions are a risk employers must address and not something workers should bear.

We began by discussing why women’s ‘workplace injuries’ remain largely unseen, but the problems working women face cannot be solved by workers’ compensation alone. Marginalization in labor, health, and social security systems is intricately intertwined within an unequal social structure, making it impossible to distill the issue into a single solution. Pondering why the lives of working women remain so invisible is akin to questioning why the lives of working people with disabilities, sexual minorities, and immigrants remain invisible, or why the pain experienced by bodies deviating from the norm in the workplace remains so poorly exposed. For working bodies to labor healthily, we must look beyond merely applying for and securing workers’ compensation. We must scrutinize and unravel the Labor Standards Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, and the narratives surrounding labor conditions, hazard recognition, and improvement—the very laws that affect workplaces and workers.

Comments