Women in the workforce: A place that comes and goes

Min Choi, MD

Activist and occupational and environmental medicine specialist

Korean Institute of Labor Safety and Health

2023

The M-curve is gone, but are the problems solved?

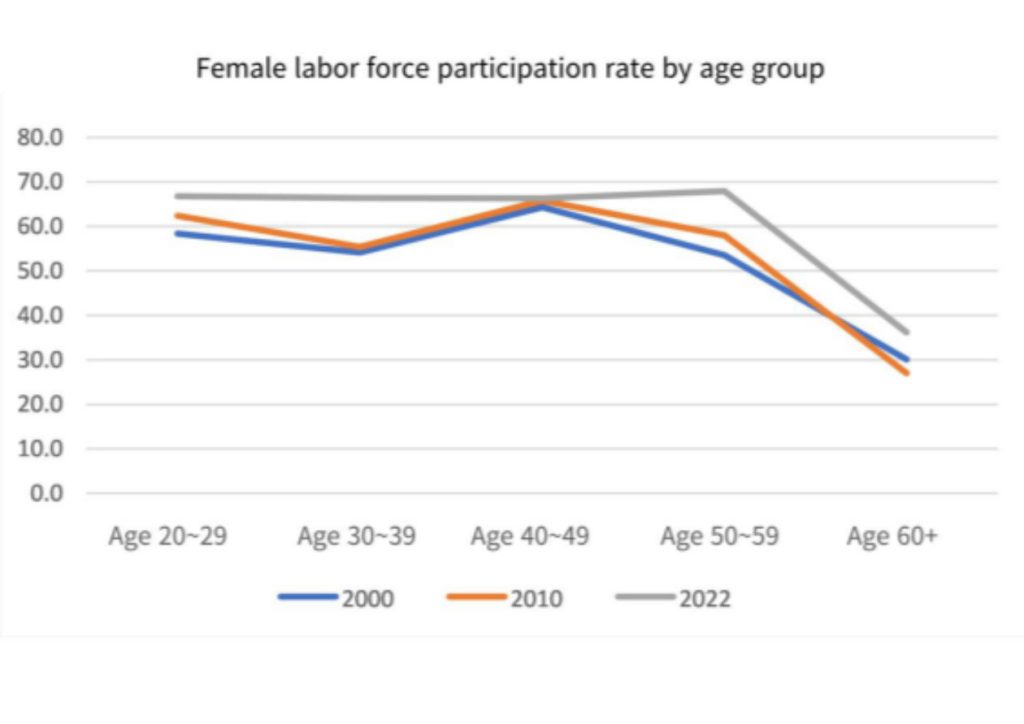

Women’s labor force participation rates by age used to follow an M-shaped curve. Women’s labor force participation rates dropped in their 30s as they focused on childbirth and childcare, and then increased in their 40s and beyond. However, the M-shaped curve is no longer evident in women’s labor force participation rates by age group. As of 2022, the labor force participation rate for women in their 20s is 67% and for women in their 30s and 40s, it is 66%.

The absolute number of women with career breaks has been declining slightly, as has the percentage of married women with career breaks. From 1.5 million women in 2020 to 1.4 million in 2022, the proportion of married women with career breaks decreased from 18% to 17%. This change is due to the increasing awareness that it is difficult to live without an income due to the high cost of housing and private education, and women’s social activities are becoming more active.

However, there is a high concern that married women’s jobs, which have been maintained in quantity, have tended to deteriorate in quality. They end up working in jobs that do not offer the same level of pay or job security as the jobs they had before marriage.

Extremely short-term jobs in her 40s

Ms. A, a continuing education teacher in a city in Gyeonggi-do province, is a middle-aged woman with a typical career break. Before marriage, she worked as a cram school instructor. After marriage, she took care of childcare and housework until her children entered elementary school. After her children entered elementary school, she still had the burden of childcare and housework, but she wanted to be “outside” again, so she started working as a volunteer “lifelong educator” at a community center. Her job was to plan educational programs for residents, as well as to promote and arrange events. She found it rewarding and fun.

After four years of working 60 hours a month for minimum wage under the “service fee” concept, she was told that the position would be hired by the city. She had high hopes that she would get a real job, but was soon disappointed. She was contracted to work 59 hours a month instead of the 60 hours she had been working. As an extremely short-time worker, she no longer had all four major insurance plans, no annual leave, and no retirement benefits. The only things that have changed since then are that the minimum wage has been changed to a living wage and she is now covered by employment insurance. Once she learned about “extremely short-time work” she realized that all the jobs around her were extremely short-time jobs.

“Not long ago, the women’s center was hiring continuing education teachers like me to provide services to counselors or women workers. They hire people to work all day, but they also hire people to manage for two days on the weekend, and they are just extremely short hours, and I have a lot of friends who do that. I have a friend who does disinfection work in the morning, and I have a friend who does housekeeping in the afternoon, and they don’t realize that they’re working extremely short hours. They don’t realize that if they work an extra hour here, they can get weekly holiday pay.”

It is no secret that the “part-timeization of women’s work” has worsened over the past decade. Women-friendly part-time jobs, that are supposed to give women more time to work at home, raise children, and take care of their families, have been at the center of the women’s jobs policies of both the presidential administrations of Park Geun-hye and Moon Jae-in.

The overwhelming availability of part-time jobs to married women has the perverse effect of making the work of married women seem secondary and less important.

In this regard, it is helpful to take a look at the book, “Housewives and Part-Time Work” (Young Kim, Busan University Press, 2020), which analyzes this issue through the lens of “housewife” part-timers in Japanese supermarkets. In Japan, if the spouse of the head of the household works in a low-wage job below a certain amount, he or she can receive a large tax deduction. Since men are usually the heads of households, under this tax system, it may be more beneficial to the household as a whole for married women to stay in low-paying jobs unless they are very high-paying jobs. This makes it appear that married women are voluntarily choosing low-paying or part-time jobs.

But it does not end there. Jobs that are expected to be dominated by married women are themselves grounds for low pay. Part-timers in supermarkets become more skilled the longer they stay, and may even take on managerial roles, but the pay gap with their full-time counterparts grows. There are no promotions or bonuses. The reason for this lack of complaints is what the author calls the “housewife agreement” because housewives themselves accept the wage gap with regular employees, saying, “We are part-time workers, we are housewives.”

In South Korea, the situation is similar. Ms. B, a married women in her 30s, quit her full-time office job at a small business when she had a child. Her irregularly employed husband became a full-time employee that year. The couple decided that it made financial sense for Ms. B to stay at home and take care of childcare and household chores rather than work in an unstable job with a monthly salary of about 2 million won (~€1369 or USD$1473). However, if she were to return to work after 10 years, it would be difficult for her to get the same job as before. In that sense, the analysis of Japanese supermarkets is equally applicable to the South Korean reality that “the future of gardening is part-timers, and the past of part-timers is full-time employees.”

Are full-time female workers in public sector organizations okay?

Some women are better off than others. These are women who work in large companies, or in the civil service or public sector. They have relatively stable employment and access to maternity and paternity leave. However, if they take parental leave, they are often overworked when they return to work. In 2017, a “working mom” government employee at the Ministry of Health and Welfare died of overexertion while juggling childcare and work. This revealed that women are struggling to survive even in the world of public service, which has always been known as a better job for women. At the time, a media outlet pointed out that the prejudice against maternity leave was also contributing to the overwork of returning workers, indicating that they were trying to take on more work because they were afraid of their employer’s resentment.

Ms. C, a woman with 15 years of experience working for a large financial company in the Yeouido area of Seoul, lives with her biological mother for childcare. After going on maternity leave, she was passed over for a promotion. Her team leader once told her, “How can I reward you well when others were working while you were away?”

It was difficult to point out to her team leader that maternity leave is guaranteed by law and that discrimination on the basis of maternity is a violation of the Equal Employment Opportunity and Work-Family Support Act. She has since taken two maternity leaves and is now stuck in her job, having already been promoted later than her peers. Her biological mother, who took care of her childcare for more than a decade, now wants to pursue her hobbies in the evenings, but even this is difficult to promise. If Ms. C cannot cope with “flexibility,” such as working overtime at short notice, she can get a low score on her job evaluation. She can only feel sorry for her mother.

In this regard, it is worth reading the book, “Career and Family” by Claudia Goldin (Thinking Power, 2021), which traces the labor of US college-educated women who struggled to achieve both “career and family” from the early 20th century to the present. Goldin explicitly analyzes how in the professional world, having a child before a major career leap can be made is often a career killer. Many professional careers are so demanding that they require “relentless intensity, irregular schedules, and long hours” in exchange for much higher pay than before. And as a society, we have seen these jobs become overwhelmingly more lucrative while wages for other jobs have stagnated. Think about the process of getting promoted above a certain level in a large company, becoming a specialist, or becoming a tenured professor at a university.

In order to increase household income, or to secure a place at the top of the increasingly dualized labor market, married couples often have to abandon equality and allow one of them to jump into these coveted jobs. As a result, the gender pay gap, inequality within couples and families, and the gap between working people grows.

Companies are the only ones who benefit when, 1) people are deprived of time to be with their families or take care of themselves, or 2) the worker must take a low-paying job so that they have time for family needs; or 3) when people are forced to do both – take on childcare and household chores and work out of necessity. We need to reject and challenge the entire status quo of overly demanding jobs and overly high pay in return for only those types of jobs. This requires women to speak together in one voice, even though the three examples above show women who seem to be too far away from each other: Ms. A, an extremely short-time worker in Gyeonggi-do; Ms. B, a full-time housewife in Gyeongsang-do; and Ms. C, a full-time employee of a financial company in Yeouido.

We need to be able to stand together against the wage gap, against a world of work that demands too much of workers’ time, and against the disappearance of women’s jobs. Organizing this solidarity is our challenge.

Comments